Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and the Middle Ages

White-Collar Clientele

Middle-aged professionals are increasingly taking to the mats to practice Brazilian jiu-jitsu, a combat sport used by mixed martial arts fighters and popularized by the Ultimate Fighting Championship. As a writer and BJJ hobbyist, I decided to explore why white-collar men are donning kimonos and wrestling each other to the ground.

Wall Street banker Alexander Benassi leads a double life. By day, the 37-year-old is a vice president at a private bank’s Chicago headquarters, working out of his suburban office from about 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. The slick-haired and eloquent Benassi helps manage the portfolios of some of the company’s wealthiest clients, including several executives of Fortune 500 companies.

Advertisement

Sometimes he even packs his gi next to a suit to train at local gyms during his downtime on business trips.

“It’s probably the only thing I can legitimately think of which I

do right now that can clear my head,” Benassi said one night after

a particularly grueling class, his face ruddy from the hour-long

workout. It was almost 9 p.m., and within an hour, he hopes to be

asleep so he can wake up before dawn to lift weights, as he does

six days a week with an ethos the former power lifter and swimmer

carries into his work.

“I really love [jiu-jitsu],” he said. “Like many people, I just wish I had found it 10 years ago.”

Benassi is part of a growing legion of middle-aged, white-collar Brazilian jiu-jitsu aficionados looking to get fit and, in some cases, test themselves in organized competition. The sport is booming in the United States after two decades of exposure in MMA’s flagship promotion, the Ultimate Fighting Championship, and competition organizers have sought to meet growing demand from BJJ practitioners of all ages and skill with tournaments across the country.

A ground fighting martial art derived from judo and traditional Japanese jiu-jitsu, BJJ, as it is often called, uses techniques intended to subdue an opponent without strikes, from hyperextending arms to choking off circulation to the head.

“There’s definitely been a huge explosion in the sport’s popularity in the last few years,” said Rener Gracie, grandson of one of BJJ’s creators, Helio Gracie, and owner of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Academy headquarters in Torrance, Calif. “By far, [middle-aged students] are our largest demographic, and that’s because there’s little impact, almost no injuries, it’s easy on the body and there’s an intellectual stimulation associated with BJJ.”

The sport’s variation of techniques and positions has led some to compare it to “human chess.” One of the most prominent competition teams is called Checkmat.

***

The growth of schools affiliated with the Gracie family, which pioneered the martial art a century ago in Brazil and first brought it to the U.S. in the 1970s, shows a clear-cut trend in the sport’s popularity, though most gyms and academies, including Ultimate Fitness, are not associated with them.

The number of Gracie academies in the U.S. has doubled to about 1,400 since 2006, and there is at least one in every state, according to Rener Gracie. More than half of the network’s 35,000 students are middle-aged; of these, a third are white-collar professionals. In Chicago, at least 20 schools, including five Gracie-affiliates, offer instruction.

Experts credit BJJ’s popularity to the rise of mixed martial arts, which is now the number four most popular sport in the U.S. among the coveted demographic of men, ages 18 to 34; it trails only football, baseball and basketball, according to research by Scarborough Sports Marketing in New York. The annual pay-per-view audience for the UFC first exceeded boxing and professional wrestling in 2006, and two years ago, the promotion signed a lucrative seven-year deal with Fox for cable and broadcast rights.

“There’s definitely a hug overlap between the popularity of MMA and Brazilian jiu-jitsu,” said Shane Logan, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of California, Davis, who last year gave a TED Talk lecture on MMA. “Had [Brazilian jiu-jitsu fighter] Royce Gracie not been such a bad-ass in these early tournaments, it’d probably be just like any [of the] other martial arts.”

Brazilian jiu-jitsu emphasizes the use of leverage and timing to overcome larger and more athletic opponents. The sport’s effective submissions and positional techniques make it an essential discipline for mixed martial artists today, distinguishing it from karate and tae kwon do, in which physical contact is minimal. It is also very accessible: BJJ can just as easily be practiced in a T-shirt and shorts as it is in a gi, the latter of which can be used as a weapon to choke and hold down an opponent; practioners can chose between training and competing with a gi and without one.

BJJ’s ascent also signals a cultural shift. Gone are the days of America’s affinity for karate and the masculine gravitas of Bruce Lee, who popularized martial arts here in the 1970s. Hollywood has been quick to reflect this change, as MMA-inspired movies like “Never Back Down” and “Warrior” have replaced Mr. Miyagi and “The Karate Kid” series -- Jaden Smith and Jackie Chan might argue otherwise -- and professional fighters like Randy Couture and Gina Carano showcase MMA’s most riveting moves; the alluring Carano is known for her on-screen flying armbar in blockbuster flicks like “The Expendables” and the “Fast and the Furious 6.”

Across the country, schools that previously only offered traditional martial arts now advertise instruction in jiu-jitsu and other combat sports. The dojo chain at which I trained karate as a boy in New York, Tiger Schulmann’s Karate, became Tiger Schulmann’s Mixed Martial Arts a few years ago.

“You have [karate] black belts who have never hit somebody or been hit and have never done anything but punch or kick air,” says Benassi, who trained karate in college. “There’s a sort of competitiveness to jiu-jitsu, you know, testing yourself.”

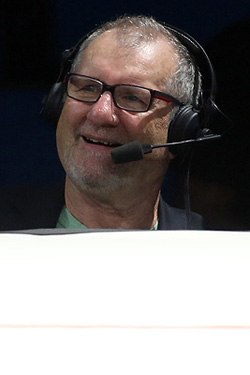

Photo: D.

Mandel/Sherdog.com

O’Neill holds the rank of black belt.

At 21, I am often the youngest on the mats at Ultimate Fitness. Half of the 90 students in the BJJ program there are over 35, and the majority of these are white-collar professionals coming in to tussle after a day at the office, according to our instructor Jeff Serafin.

“They can’t go to work with a concussion or bloody nose,” he said. “Jiu-jitsu allows those who like MMA or competitive sports to train and compete.”

Benassi, a former power lifter who had to stop following a spell of back and knee injuries, took up Thai kickboxing for a few months after watching the UFC one night. He quit smoking and practiced the sport for about three months while he ran his own hedge fund in Peoria, Ill. After his current company tapped him, he dropped kickboxing for BJJ.

“When you’re dealing with the client base that I deal with, you can’t really show up to meetings with black eyes or broken noses or things like that, so I had to stop,” he said. “At the time, I had started training Brazilian jiu-jitsu, as well, so I just switched full time to that.”

A few months ago, Benassi -- who holds a white belt, the lowest of eight ranks -- took his hobby of two years a step further. He began competing at regional tournaments that draw hundreds of participants from across the country; sweat, pain and sometimes blood culminate in only three men at the winner’s podium for every weight and rank division. He has found success, too. In March, he took home the gold in the super heavyweight division for white belts over 35 at the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation’s Chicago Open, this after falling short in his previous two tournament outings. He beat his first two opponents by points in close matches, before winning his final match with an armbar.

“It’s almost meditative in the sense that you can do it and not worry about what’s going on at work.” Benassi said. “You’re not thinking about anything but that weight on top of you.”

***

More than a sport or an organized chance to fight, Brazilian jiu-jitsu is a fraternity that opens doors and friendships across the country, my teammate, Thomas Mulroy, told me one night as he changed back into a button-down shirt and slacks. Mulroy, 40, is an attorney who represents hospitals in medical malpractice suits, and, like Benassi, he often trains where he travels for business, including in Texas, New York and California -- a state considered to be a BJJ mecca. Mulroy, a purple belt who occasionally competes, appreciates what he calls the philosophical side of BJJ.

“It will translate over to your regular life,” he said. “So when you have setbacks in life, you can refer to those setbacks you had in jiu-jitsu to realize that you do get through these things, and having peaks and valleys is a natural part of progressing in life, no matter what you’re doing.”

David Mayeda, a sociology professor at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, says BJJ offers white-collar men a new lease on life by serving as an outlet for testosterone-fueled aggression and comradery. Mayeda studies the relationship between mixed martial arts and masculinity and co-authored the book “Fighting for Acceptance: Mixed Martial Arts and Violence in American Society.” He has also fought on the amateur MMA circuits in the name of research.

“Men who are not engaged in physically laborious labor are looking for ways to redefine their manhood,” Mayeda said. “It gives them a chance to establish a sense of manhood they don’t necessarily have when they’re lawyers, dentists and bankers, for instance.”

Sound familiar? In the 1999 cult classic “Fight Club,” Edward Norton plays an unnamed, pencil-pushing narrator who runs a fight club created by his alter ego, portrayed by Brad Pitt. The group’s quest to reclaim their masculinity and combat a commercialized culture soon devolves into an anarchist attempt to topple corporate America. In one memorable scene, a black-eyed Norton bares his bloodied teeth in response to a question during an office meeting, leaving his co-workers and supervisor aghast.

Copycats sprang up in schools, neighborhoods and even workplaces in the film’s wake. A 2006 Associated Press story describes the gruesome escapades of a Silicon Valley techies fight club. Despite the movie’s twist at the end, there are strong similarities between Chuck Palahniuk’s creation and the pugnacious camaraderie of Brazilian jiu-jitsu, though unlike Norton’s character, Benassi and most of the other white-collar men on the mats are trying to avoid black eyes and raised eyebrows at the water cooler.

How much did “Fight Club” -- which has been called a manifesto for a generation of boys and men looking to reconnect with their masculinity -- contribute to the popularity of BJJ and mixed martial arts today?

“There’s definitely that search for manhood that’s lost when you live in a service economy,” Mayeda said.

However, he gives the UFC most of the credit for the rise of both. During the hodgepodge melees of the promotion’s early tournaments, slender BJJ black belt Royce Gracie dominated his opponents -- boxers, kickboxers, professional wrestlers and karate black belts -- with a mix of grappling and submissions. Fight fans across the world were captivated, and many BJJ fighters from Brazil flocked to the U.S. to teach as demand grew, particularly to California, Rener Gracie said.

In 2005, Brazilian jiu-jitsu gained mainstream exposure when “The Ultimate Fighter” reality show made its way to Spike TV, Mayeda said. Soon after the show’s popularity became apparent, Ultimate Fitness began to offer BJJ in addition to boxing -- its previous focus -- in order to capitalize on BJJ’s trendiness, which, according to Serafin, has grown along with the UFC.

Finish Reading » “This is a just a metaphor for my life. I’m a better guy with jiu-jitsu. What I do in jiu-jitsu reflects how I go about life.”