Mayeda Examines MMA’s Role in Society

Feb 25, 2009

Fights inside and outside the cage and ring fall under the mixed

martial arts umbrella. For David Mayeda, MMA has become as much

about responsibility as excitement.

The “human cockfighting” phrase still reverberates, despite support from mainstream advertisers like Nike, Bud Light and Microsoft. Mayeda, who earned his PhD in American Studies from the University of Hawaii, set out to explore MMA’s place in society in 2005 after coming to know the sport through “The Ultimate Fighter” reality series.

“I knew, even though I was seduced by mixed martial arts as a fan,

it potentially could have differing effects on society in terms of

violence,” said Mayeda, who has placed his academic focus on

violence prevention geared toward youth.

“Fighting for Acceptance: Mixed Martial Artists and Violence in American Society” was published in February 2008. Mayeda took his theses from print to film when he directed, co-produced and narrated the documentary “MMA 808: Inside Hawaii’s Fight Game,” which was later derived from his book.

MMA enthusiasts charge Mayeda with taking the sport backward by acknowledging its warts. Detractors, on the other hand, view him as an apologist.

The Hawaiian recognizes reluctance to be honest about the sport because of the obstacles it has had to overcome to become accepted in the mainstream. If the UFC applies its marketing muscle to social issues, it can make a visible impact, according to Mayeda. He was pleased with UFC Fight Night 16 “Fight for the Troops” in December and hopes the show serves as the first step in significant social involvement.

Balance between violence and the “feel good” story seems paramount, and the former high school football player points to the NFL as a potential model for the UFC. That organization -- the most popular and powerful professional sports entity in America -- also walks arm-in-arm with violence.

“They have really strong charitable organizations that they promote during their commercials during their games,” Mayeda said.

Responsibility does not rest solely with the UFC. If an MMA promotion can profit from a community, it can give back to it, as well. Mayeda offered one startling example of MMA doing its best to curb violence. In Kailua, Hawaii, more than a year ago, a man beat his ex-girlfriend to death with the butt of his gun. MMA Hawaii executives who run MMA Hawaii Magazine and mmahawaii.com recognized the perpetrator as one of the spectators at an event they sponsored.

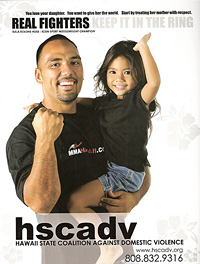

In response, MMA Hawaii initiated partnerships with the Hawaii State Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Mothers Against Drunk Driving. MMA Hawaii Magazine also enlisted Icon Sport middleweight champion Kala Hose and had him pose with his daughter under the caption: “You love your daughter. You want to give her the world. Start by treating her mother with respect. Real fighters keep it in the ring.” Mayeda thinks responsible fighters should speak out against domestic violence, drunken driving, substance abuse and other social ailments more often.

Even with island MMA in recovery after the extended absence of Rumble on the Rock and Icon Sport -- Mayeda believes MMA was more popular in 2001 than it is now -- ads like the one involving Hose do more than educate fans; they educate lawmakers, too. It frustrates Mayeda that similar campaigns are not already fixtures in the sport.

“I think those icons need to be pushed, not just as athletes but as humanitarians, as well,” he said. “I think that can do a lot to change the culture of mixed martial arts.”

Mayeda thinks MMA has the power to use its popularity to bring about positive change. He and Antonio McKee -- a former International Fight League standout who also works with children in his community -- agree that youth violence prevention programs involving MMA appeal to at-risk kids because it provides a release through which they can draw on their physical abilities. However, advancing the culture of MMA has many obstacles, and one -- “The Ultimate Fighter” -- stands out above all the rest.

Each installment of the Spike TV reality series brings promising talent to the UFC. What happens along the way perturbs Mayeda. The fights may not be official, but UFC President Dana White’s presence -- along with prominent fighters serving as coaches -- makes the show a representation of the UFC, in particular, and MMA, in general. It has a heavy influence on first impressions.

“They already have the [male] 20- and 30-something demographic kind of hooked,” Mayeda said. “So I don’t know that ‘The Ultimate Fighter’ is bringing new fans from that demographic. They need to be reaching out to an older demographic, men and women.”

Mayeda sees it as a tug-of-war between long-term investment and a shortsighted play for ratings and cash. He points again to the NFL, which puts together family-friendly events despite the inherent violence associated with football. MMA role models abound, according to Mayeda.

“[Rosi Sexton has] a 2-year-old child and [is an] 8-1 mixed martial artist with a PhD,” he said.

Mayeda now watches traditional MMA programming as he continues his advocacy for a sport still struggling to find its identity. The more he speaks out, the more criticism he receives. His is a thankless job. Mayeda no longer watches “The Ultimate Fighter,” even though it brought him to MMA. He suggests Junie Allen Browning’s antics on the most recent season countered the UFC’s efforts to keep negative images -- like the infamous Noah Thomas-Marlon Sims street fight on season five -- under wraps. Mixed signals are being sent.

“It’s hard to reconcile that inconsistency,” Mayeda said. “It’s like ‘Jackass’ the movie for the series. They’re really helping to create that ambiance. I just don’t understand anymore. They should have learned from TUF 1. They’re not evolving. They’re devolving.”

Mayeda wants MMA to borrow from traditional martial arts. Teach it for discipline, self defense and self-esteem building. Teach younger students more grappling than striking. Build family relationships and educational goals.

“Those are the things that martial arts schools are known for doing,” he said. “If MMA schools can capture that identity and really pursue those goals, it’ll have a much easier time gaining acceptance across the country.”

The “human cockfighting” phrase still reverberates, despite support from mainstream advertisers like Nike, Bud Light and Microsoft. Mayeda, who earned his PhD in American Studies from the University of Hawaii, set out to explore MMA’s place in society in 2005 after coming to know the sport through “The Ultimate Fighter” reality series.

Advertisement

“Fighting for Acceptance: Mixed Martial Artists and Violence in American Society” was published in February 2008. Mayeda took his theses from print to film when he directed, co-produced and narrated the documentary “MMA 808: Inside Hawaii’s Fight Game,” which was later derived from his book.

“I’m going to stick to my assertion that because MMA is the closest

thing to the complete sport of fighting, it holds -- the sport as a

whole holds -- a broader social responsibility,” he said. “That

overlap between MMA and street school or domestic violence is the

most striking concern for me socially. I’d like to see the MMA

community take a broader responsibility in distancing the sport

from those types of violence and sending out the right social

messages to prevent those types of violence.”

MMA enthusiasts charge Mayeda with taking the sport backward by acknowledging its warts. Detractors, on the other hand, view him as an apologist.

The Hawaiian recognizes reluctance to be honest about the sport because of the obstacles it has had to overcome to become accepted in the mainstream. If the UFC applies its marketing muscle to social issues, it can make a visible impact, according to Mayeda. He was pleased with UFC Fight Night 16 “Fight for the Troops” in December and hopes the show serves as the first step in significant social involvement.

Balance between violence and the “feel good” story seems paramount, and the former high school football player points to the NFL as a potential model for the UFC. That organization -- the most popular and powerful professional sports entity in America -- also walks arm-in-arm with violence.

“They have really strong charitable organizations that they promote during their commercials during their games,” Mayeda said.

Responsibility does not rest solely with the UFC. If an MMA promotion can profit from a community, it can give back to it, as well. Mayeda offered one startling example of MMA doing its best to curb violence. In Kailua, Hawaii, more than a year ago, a man beat his ex-girlfriend to death with the butt of his gun. MMA Hawaii executives who run MMA Hawaii Magazine and mmahawaii.com recognized the perpetrator as one of the spectators at an event they sponsored.

In response, MMA Hawaii initiated partnerships with the Hawaii State Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Mothers Against Drunk Driving. MMA Hawaii Magazine also enlisted Icon Sport middleweight champion Kala Hose and had him pose with his daughter under the caption: “You love your daughter. You want to give her the world. Start by treating her mother with respect. Real fighters keep it in the ring.” Mayeda thinks responsible fighters should speak out against domestic violence, drunken driving, substance abuse and other social ailments more often.

Even with island MMA in recovery after the extended absence of Rumble on the Rock and Icon Sport -- Mayeda believes MMA was more popular in 2001 than it is now -- ads like the one involving Hose do more than educate fans; they educate lawmakers, too. It frustrates Mayeda that similar campaigns are not already fixtures in the sport.

“I think those icons need to be pushed, not just as athletes but as humanitarians, as well,” he said. “I think that can do a lot to change the culture of mixed martial arts.”

Mayeda thinks MMA has the power to use its popularity to bring about positive change. He and Antonio McKee -- a former International Fight League standout who also works with children in his community -- agree that youth violence prevention programs involving MMA appeal to at-risk kids because it provides a release through which they can draw on their physical abilities. However, advancing the culture of MMA has many obstacles, and one -- “The Ultimate Fighter” -- stands out above all the rest.

Each installment of the Spike TV reality series brings promising talent to the UFC. What happens along the way perturbs Mayeda. The fights may not be official, but UFC President Dana White’s presence -- along with prominent fighters serving as coaches -- makes the show a representation of the UFC, in particular, and MMA, in general. It has a heavy influence on first impressions.

“They already have the [male] 20- and 30-something demographic kind of hooked,” Mayeda said. “So I don’t know that ‘The Ultimate Fighter’ is bringing new fans from that demographic. They need to be reaching out to an older demographic, men and women.”

Mayeda sees it as a tug-of-war between long-term investment and a shortsighted play for ratings and cash. He points again to the NFL, which puts together family-friendly events despite the inherent violence associated with football. MMA role models abound, according to Mayeda.

“[Rosi Sexton has] a 2-year-old child and [is an] 8-1 mixed martial artist with a PhD,” he said.

Mayeda now watches traditional MMA programming as he continues his advocacy for a sport still struggling to find its identity. The more he speaks out, the more criticism he receives. His is a thankless job. Mayeda no longer watches “The Ultimate Fighter,” even though it brought him to MMA. He suggests Junie Allen Browning’s antics on the most recent season countered the UFC’s efforts to keep negative images -- like the infamous Noah Thomas-Marlon Sims street fight on season five -- under wraps. Mixed signals are being sent.

“It’s hard to reconcile that inconsistency,” Mayeda said. “It’s like ‘Jackass’ the movie for the series. They’re really helping to create that ambiance. I just don’t understand anymore. They should have learned from TUF 1. They’re not evolving. They’re devolving.”

Mayeda wants MMA to borrow from traditional martial arts. Teach it for discipline, self defense and self-esteem building. Teach younger students more grappling than striking. Build family relationships and educational goals.

“Those are the things that martial arts schools are known for doing,” he said. “If MMA schools can capture that identity and really pursue those goals, it’ll have a much easier time gaining acceptance across the country.”