* * *

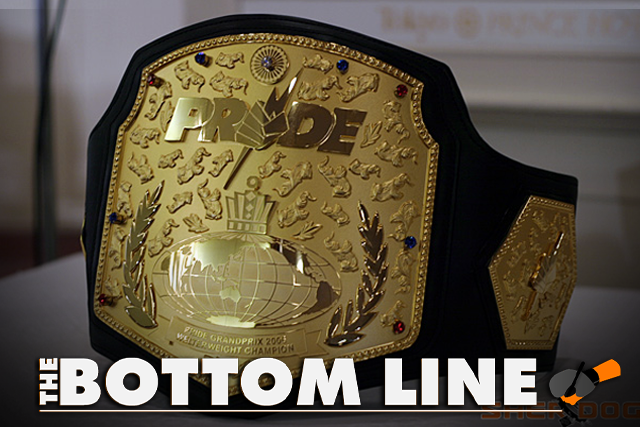

It was 25 years ago today that Pride Fighting Championships, one of the two most influential organizations in MMA history, ran its first event. For years Pride was the gold standard in MMA, both for its major-league presentation and for the most talented roster of fighters during a period when the Ultimate Fighting Championship was still recovering from a concerted effort to destroy the company—and the sport—in the United States.

To this day, what drove Pride FC’s popularity is misunderstood in many circles. It’s sometimes asserted that Pride rose up because Rickson Gracie was a major star to the Japanese public or that the glory days of the promotion were driven by the popularity of Fedor Emelianenko. In fact, Pride was an offshoot of Japanese professional wrestling and driven by intrigue about how tough Japan’s most popular professional wrestlers really were.

The story of Pride is best understood by going back to the early days of Japanese professional wrestling, when top Japanese superstar Rikidozan legitimately knocked the legendary judoka Masahiko Kimura unconscious with punches in a pro wrestling ring three years after Kimura famously submitted Helio Gracie in Rio de Janeiro. Japanese pro wrestling, a hugely popular TV ratings phenomenon, was driven by post-World War II Japanese wrestlers fighting for national pride against star fighters of different disciplines from around the world. The recently departed Antonio Inoki’s mixed fight with Muhammad Ali was the most famous of these matches, but far from unique.

Nobuhiko Takada in the 1990s was the latest wrestler to take up this mantle for the popular UWFI promotion. UWFI was less popular than the more traditional New Japan Pro Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling promotions but it featured a more realistic looking style. UWFI presented itself as real, but was in fact closer to a worked version of the rival Pancrase organization that Takada’s former training partners and rivals Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki had founded.

Takada, in an effort to get over that he was realer than other pro wrestling champions, issued grandstand challenges to other wrestlers from around the world. One of his grandstand challenges was to Rickson Gracie, as the Gracie family had become known in Japan in large part through the early UFC events where Rickson’s brother Royce had submitted Pancrase star Ken Shamrock. As part of this grandstanding, UWFI undercard wrestler Yoji Anjo went to Los Angeles to challenge Gracie. It did not go as planned as Gracie accepted the challenge with no notice and proceeded to pummel Anjo. The Japanese press with Anjo didn’t get to see the fight itself but did see the aftermath and Anjo was permanently disgraced.

Before he beat Anjo into the ground, Gracie had been only a secondary or tertiary consideration to UWFI fans. After the Anjo incident, pro wrestling fans felt that Takada needed to avenge his company’s honor. It was a prototypical pro wrestling angle that had been done countless times in the past: the foreign menace beats up on the lower level Japanese star and it’s now up to the big Japanese star to get revenge. Takada, of course, had no interest in doing any such thing. He knew exactly how it would go for him. However, years later as the popularity of Takada declined and UWFI went out of business, Takada had fewer options and was willing to take a big paycheck to fight Gracie for real.

That first Takada-Gracie fight was what built Pride. In the early days of Pride, there was a marked difference between the events that featured Takada and the events that didn’t have Takada. The Takada events drew much better. However, as fans realized Takada couldn’t really fight, it became harder to build around him. Luckily for Pride, there was another UWFI undercard wrestler who would take up Takada’s fight and go after the Gracies: Kazushi Sakuraba.

Sakuraba’s rivalry with the Gracies was Pride’s most important feud. It made Sakuraba a superstar and Pride rode that for the rest of its existence, with Sakuraba featuring on two-thirds of Pride events that drew an announced attendance of over 35,000 fans. Pride’s other top drawing cards included other pro wrestlers like Kiyoshi Tamura and Naoya Ogawa, along with fighters that became stars through repeatedly facing pro wrestlers, including Wanderlei Silva and Mirko “Cro Cop” Filipovic. Foreign fans delighted at the high production values, the loaded grand prix tournaments and the elite fighters but the money that drove the product domestically was Japanese fighting spirit symbolized by wrestlers like Inoki on down to Sakuraba against the world’s best.

Despite the popular saying “Pride Never Die,” the promotion’s days feel long past now. Pride has been dead for significantly longer than it was alive. The UFC approach to promotion and matchmaking has become the standard worldwide, largely embraced by its competitors as well. When ESPN did a feature a few months ago on the greatest fighters by year from 1993 to the present, not a single fighter from Pride made the list.

Matt Hughes vs. Frank Trigg 2 and Wanderlei Silva vs. Quinton “Rampage” Jackson 2 took place less than six months apart in 2004-2005. At the time, Silva-Jackson felt orders of magnitude bigger. If you surveyed MMA fans today, Hughes-Trigg would probably be better recognized and remembered. It’s a shame, but that’s just the nature of history. Events are remembered differently than they were. That’s certainly the case with Pride, which at least makes getting to have experienced it as it happened all the more special.