PROLOGUE | PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5

PROLOGUE

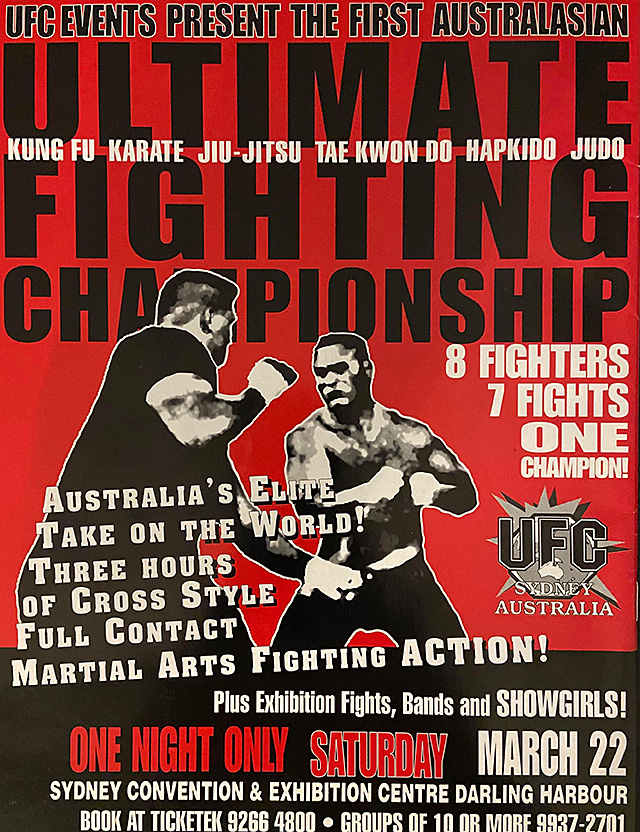

A UFC event you never heard of took place at the Darling Harbor Exhibition and Convention Center in Sydney on March 22, 1997. Eight fighters from the United States, Brazil, Canada, Australia and New Zealand converged under the bright lights of the Sydney metropolis for a $25,000 winner-take-all openweight tournament. The last man standing would receive a novelty check and a belt emblazoned with three words: “Ultimate Fighting Championship.”The promotional posters invited participants to witness “the first Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship.” Many spectators among the 5,000-strong crowd had that impression when they purchased their seats. That was reinforced while fights took place in a hastily assembled octagonal cage. Zane Frazier, a veteran of UFC 1 and UFC 9, was in the original lineup of tournament participants before pulling out with an injury at the eleventh hour. This mimicry was so flagrant that at least one of the competitors thought he was competing in the first Ultimate Fighting Championship event in Australia.

The original promotional poster was featured in Blitz magazine and later in a trademark lawsuit the Semaphore Entertainment Group brought against Randy Bable. Provided by Matt Rocca.

Semaphore Entertainment Group, which owned and operated the “as real as it gets” UFC from 1993 to 2001, engaged lawyers to protect its intellectual property and stop American promoter Randy Bable from holding the event. Racing alongside them with similar intentions was the New South Wales police force, which wanted to block the tournament on the grounds that it was not sanctioned by the state’s boxing authority.

Still, packaging Bable’s “UFC” into VHS cassette tapes and distributing them to fight fans was apparently worth the risk to a figure one fighter likened to Don King for his flair and flamboyance. The American oversaw it all on a wing, a prayer and with a quarter million dollars on the line. Against this backdrop of legal proceedings, the specter of police intervention and a hostile local media, the first-time promoter somehow pulled off seven bareknuckle NHB bouts.

The endeavor was financially calamitous for Bable, but it launched the careers of Australian MMA pioneers and provided future icons, including tournament winner Mario Sperry, a meaningful stop on their respective journeys. Sperry remembers the Australasian UFC as the night he fought “one thousand cats” because of the sandpaper-like canvas.

Future UFC, Pride Fighting Championships and Rings stalwarts were also featured in the cage, and commentator Michael Schiavello called the action, which was seamlessly interspersed with choreographed performances by the exotic dance troupe “Fever Girls” and the stylings of a live rock band.

“Just talking to you now about it, I’ve got a smile on my face,” said former Australian kickboxing champion Mark Castagnini, the second half of the broadcast team alongside Schiavello. “At the time, I was the general manager and head of sales and marketing of the Blitz Magazine. Randy came to me wanting to book a whole bunch of ads. He said he wanted to do something that had never been seen before in this country: guys fighting in a cage.”

Bable’s fights followed the lead of Battlecade Extreme Fighting, an early UFC competitor, by segmenting contests into three five-minute rounds. It was also the first to use a mounted referee camera later popularized by Pride. For the few months immediately prior to the event, it looked like his venture would take off and truly establish NHB as a legitimate entertainment product in this part of the world.

PART 1: 'ULTIMATE FIGHTING' HEADS DOWN UNDER

In early 1997, “no holds barred” entered its dark age. After becoming a breakout hit on pay-per-view on the back of UFC 1 tournament winner Royce Gracie and a subsequent influx of marketable headliners that included Ken Shamrock, Dan Severn and David “Tank” Abbott, the Ultimate Fighting Championship was unwittingly cast as an antagonist in a culture war being waged across America against violent video games, music and television content.

Arizona senator and future Republican presidential nominee John McCain famously spearheaded a fervent letter-writing and political campaign to strangle caged combat while it was still in its infancy. McCain infamously compared NHB to “human cockfighting” and successfully convinced cable operators to drop the burgeoning franchise after UFC 12 in 1997.

That same event would see a promotion on the run, as the UFC was forced to change venues—and states—on 48 hours’ notice in response to a court ruling that effectively banned NHB in New York. Across the United States, governors lined up to exile shows or regulate them to the point where they were unrecognizable; and while there was a growing appetite for the product from spectators, there were progressively fewer avenues to sell it, as skyrocketing legal fees hung like albatrosses around the UFC’s neck.

The organization’s visibility and profitability were on fast, downward trajectories. Facing political opposition in every territory where it tried to throw events, the moral panic around “no rules” exhibitions had been fueled by the UFC’s morbid potential, which was marketed as a way to sell more pay-per-views. None of that kept would-be competitors from emerging around the world.

Entering the fray was commercial builder Randy Bable, an American expat who had found himself in Sydney after chasing his future wife from California as a young man in 1987. Transfixed by the lucrative potential of NHB, Bable schemed to bring the octagon and some of the world’s best NHB fighters to his adopted home of Sydney for a one-night extravaganza. He hoped it would jumpstart a franchise and bring the martial arts “revolution” to Oceania, all while making a few bucks in the process.

* * *

It started two years earlier in Bable’s office in Sydney’s Chinatown. A fellow yank, the friend of one of Bable’s work associates in the commercial building sector, breathlessly presented him with VHS tapes of UFC 2 and UFC 3, along with a proposition to bring an openweight “ultimate fighting” tournament to the Sydney metropolis.

Bable dabbled in music promotion alongside his first love of real estate and knew a thing or two about live events. He was intrigued by the idea and started scouring the martial arts community for more information on a burgeoning sport turning heads and generating controversy back in America.

With email and Internet forums not yet useful tools, Bable spent months stalking newsagents and video stores for magazines and VHS tapes to educate himself about the phenomenon known primarily by a string of superlatives: “ultimate,” “extreme” and “anything goes.” Years later, Bable described his vision as the sporting equivalent of the film “Any Given Sunday.” He wanted the kind of spectacle that kept people in the bleachers or at home captivated for the full running time.

“I wanted to create something that, as soon as somebody sat down, as soon as the music started, it was 100 percent go time all the way through,” he recounted, still effervescent about the concept more than two decades on. “There would be hot, sexy girls in between the fights and music from the live band. It wasn’t just the fighters but this huge event, with all these elements tied together to make a huge spectacle.”

Bable’s next step was to incorporate a company, UFC Events Pty Ltd, and contact a commercial lawyer. Then, he pulled out his phone book and started dialing.

(+ Enlarge) | Photo: Wikimedia commons

Ken Shamrock was an early star in the

Ultimate Fighting Championship and

Pancrase organizations and takes much

of the credit for MMA’s contemporary

success. Fighters from his famed Lion’s

Den fight camp would compete in the

“Australasian UFC” event in March 1997.

In the mid 1990s, Australia’s martial arts scene was dominated by heavyweight kickboxing, with the sport in the midst of an unprecedented—and ultimately short-lived—golden age on the backs of K-1 stalwarts Stan “The Man” Longinidis, Sam Greco and Adam Watt. The trio’s international exploits buoyed a thriving kickboxing scene centered mainly in Melbourne. Boxing, a sport in which Australia had punched well above its weight, was continuing to produce championship-level exports, Jeff Fench, Kostya Tszyu and Jeff “Hitman” Harding among them.

Australia lived up to its historical reputation as a land of bruising strikers, but that was married to a nonexistent wrestling or ground fighting culture. With the exception of five Australians who had been recruited to compete in Japan’s Pancrase promotion and assembled a collective record of 7-24 from 1994 to 1997—they were likened to sacrificial lambs facing off against Ken Shamrock and Masakatsu Funaki—NHB was an uncharted frontier Down Under. For that reason, when Bable reached out to the principals in Australian kickboxing and martial arts with the idea for an openweight, bareknuckle, cross-style martial arts tournament in the heart of Sydney, they reacted with skepticism.

“I had dealings with all of the key players in martial arts in Australia, all the industry leaders,” recalled Mark Castagnini, the general manager of the Blitz Australasia Martial Arts Magazine. He was also an Australian kickboxing champion and novice ringside commentator when he first took Bable’s call. “This guy pops up. He comes into town, talking big things. I asked around, and no one knew him or where he came from. The trepidation around what he was proposing was there from the start.”

Castagnini’s circumspection led him to ask for advance payment when Bable bought ad space promoting the event inside the pages of Blitz.

“Back then, if a fast-talking American comes to town and starts throwing around big figures, something doesn’t smell right,” Castagnini said. “If it’s too good to be true, it probably is. Back then, the martial arts community was very tight. Everyone knew everyone, and nobody knew Randy.”

Meanwhile, Bable talked about building a franchise to rival Australian rules football and getting broadcast deals with the major networks—goals that were considered precocious at best and delusional at worst. Because fight promotion is an industry with no shortage of charlatans, many initially wrote off Bable’s pitch as being dead on arrival.

What the aspiring promoter lacked in street cred, he made up for with persistence. Bable consulted with anyone who took his call. Shaking trees across the kickboxing, professional wrestling and “shoot fighting” worlds, he learned everything he could about rules sets, the logistics of fight promotion and the mechanics of officiating. Slowly but surely, Bable built a team of martial arts veterans who were vital to discharging responsibilities on the night of March 22 and the weeks leading up to it.

By the time Bable had secured a venue for the event and began working with his lawyer to draft contracts for fighters and a litany of other services—video production, the assembly of an octagonal cage and a team of exotic dancers—early doubts held among Bable’s inner circle began to disappear.

* * *

The first UFC tournaments were populated by fighters of different nationalities and points on the martial arts spectrum. The promotion struck gold with the rivalry between the Brazilian babyface Royce Gracie and “Captain America” Ken Shamrock. Likewise, in Japan, Pancrase was sending scouts across America, Europe and Oceania to populate its event schedule, maintaining a revolving-door-roster of international foils and the occasional babyface to square off against their Japanese stars.

It is little wonder then that when Bable began working on this event, he settled on an eight-man, winner-takes-all tournament, envisioning competitors from across the globe squaring off against Australian and New Zealand counterparts. Calls went out to established fight camps like the Lion’s Den, and advertisements loudly inviting expressions of interests from fighters were placed in Blitz Magazine. Word of mouth spread, and slowly but surely, the bracket started filling out

“One day, I’m reading the Blitz Magazine and up pops up this full-page ad,” recalled Elvis Sinosic, a young grappler who moved from Canberra to Sydney in search of better martial arts training. “‘Do you want to fight in the UFC? Australasian UFC coming to Australia—interested fighters please apply here.’ I knew absolutely nothing about [Bable], but I was drawn by the UFC. I didn’t even think about it before I contacted him.”

One of the first promotional posters for the event in late 1996, published in Blitz Magazine. Eventual tournament participants Elvis Sinosic recalls jumping at the chance to compete in the UFC. He would later find out that Bable had no connection to Semaphore Entertainment Group and was using its name without permission. From Blitz Magazine (Volume 10, Issue 12)

Sinosic was initially rebuffed due to his lack of NHB experience. Self-taught grappler Neil Bodycote, from Newcastle, received a similarly lukewarm reception on the first try before being called up closer to the event. An early, incomplete iteration of the bracket published in Blitz boasted the inclusion of UFC 3 winner Steve Jennum; European Thai champion Richie Bezems, from Holland; onetime UFC competitor Gerry Harris; Chris Haseman, who debuted in Japan’s Rings promotion in January 1996 and had an NHB record of 1-1; Nelson Taione, billed as one of Australia’s best kickboxing and taekwondo exponents; and Hiriwa Te Rangi, who won a string of Australian national zen do kai and kickboxing titles.

Over the weeks and months leading up from the announcement of the event in late 1996, numerous fighters would float in and out of the tournament’s orbit, and the bracket would not be finalized until three hours before the start of the show.

* * *

The Australian media had been covering the political furor surrounding the UFC in America and amplified the more inflammatory talking points on slow news days, including the memory-searing “human cockfighting” line. A January 1996 opinion piece published in the Sydney Morning Herald, one of Australia’s most popular mastheads, opined that the kind of barbarism on display in the UFC’s Octagon “might not have happened in the good old days, when the ultimate fight was between capitalism and communism and Americans had plenty of communists to fight.” A feature published two months later quoted critics who described the fights as pandering “to the basest of human sensibilities.”

“I knew there was going to be a little bit of blowback, but nothing like what I got when I announced it,” Bable said. “I was trying to keep the positive spin with the press and everything. You look at some of the articles. They weren’t all that favorable to what I was trying to bring into Australia.”

Unflattering and frequently uninformed media commentary precipitated Bable’s second major hurdle: The Boxing Authority of New South Wales, a statutory body responsible for regulating boxing, kickboxing and wrestling. It had a reputation for red tape.

“Whereas in Victoria and Queensland you could elbow and knee in muay Thai and kickboxing matches, [The New South Wales Authority] made kickboxing [fighters] wear shin guards and banned knees,” recalled Bain Stewart, a kickboxer-turned-promoter who consulted Bable on the event and was manager to an eventual tournament finalist in Haseman. “The police were always trying to get people to wear protective equipment and all that sort of stuff, which would take away from the fight, and here Randy was trying to put on a bareknuckle cage fight.”

Another plug for the “Australasian UFC” event in Blitz magazine (Issue 11, Volume 12). Commentator Michael Schiavello says that the magazine was “all in” on the event and what it promised for Australian martial arts.

Bable’s workaround was multipronged and with an eye on the future. He created the “Ultimate Fighting Association,” which was defined in the fighter contracts as “the governing body which governs the conduct of the [22 March 1997] Event throughout Australasia” and was reported to included members “with more than 50 years combined martial arts training” in addition to medical practitioners. It was a move right out of Art Davie’s handbook.

The originator of the first UFC tournament had created the “International Fight Council” to oversee the development and enforcement of the original “laws of the octagon” in 1993. In both cases, the body was controlled by the promotion. Bable stood as chairman of the UFA. This was more palatable to lawmakers and the media, who were used to the three-letter sanctioning bodies from the boxing and kickboxing worlds. Bable believed the association could oversee and officiate other NHB promotions in Australia long term and even play a mediating role with overseas organizations for the purposes of cross-promotion.

However, first came establishing credibility with the putative regulator, so Bable extended an olive branch and invited the state-appointed members to provide input on the rules. This triggered a lengthy process that would last right up until the day of the event, with last-minute changes, including a request that fighters wore modified gloves. It played out against the potential of the police shutting down the event. Bable maintained that the Authority did not have any legislative power to regulate the fights, going so far as to require fighters to warrant in their contracts that they were not “a prescribed boxer, kickboxer nor wrestler” within the meaning of the statute that created the Authority.

“Randy was smart enough to get [the Authority] involved to avoid burning bridges completely,” said Cameron Quinn, who was engaged as the referee of the event and had experience dealing with the Authority as a kickboxing official. “It was almost like they were saving face. By their presence, they felt as though they had some jurisdictional authority, when in actual fact, they had nothing because the wording of their own legislation had cut them out of it.”

Then came a cease-and-desist letter from SEG on Feb. 28, 1997 that accused Bable of a string of trademark infringements, including the use of the octagonal cage, logos which were materially similar to SEG’s and passing his company off as the UFC. For what felt like the thousandth time that month, Bable picked up the phone and called his lawyer.

Continue Reading » Part 2: Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery