Let There Be Fight

Pioneers Emerge

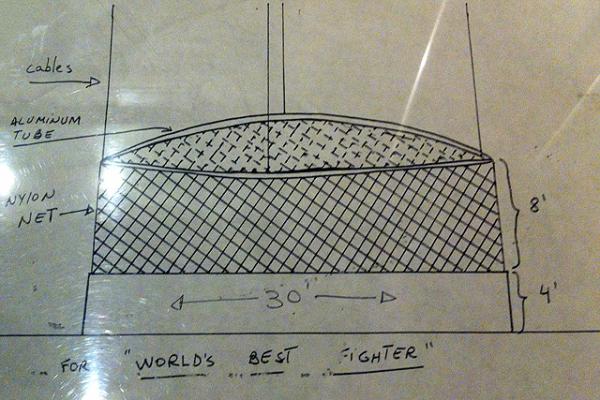

The

blueprints for the UFC's Octagon are now a unique historical

document. | Photo: Dave Mandel/Sherdog.com

There was another major choice that had to be made. A few working names for the event were bandied about. One was “War of the Worlds” and the other was the “World’s Best Fighter.” No one could pin down anything definitive, anything with bite, until Semaphore’s Michael Abramson blurted out almost casually, “How about the ultimate fighting championship?”

McLaren called Davie with the idea, but Davie, an old advertising exec, was a little concerned with the three-word name. He knew that third words were frequently forgotten. Despite his reservations, Davie let Meyrowitz know and the two settled on the moniker. It passed. Through time, the acronym UFC has reached an iconic universal stature. With the name and venue set, Davie and his group waded through another challenge. What exactly were the fighters going to compete in?

Advertisement

“No, no, no, none of that stuff was really going to be used, believe me,” said “Big” John McCarthy, the longtime respected MMA referee who worked and sparred with Royce Gracie and was there at Ground Zero before UFC 1 took off. “We thought about putting a moat in there, and they did talk about electrifying the fence. The whole thing was Jason Cusson’s idea, the guy who put the octagon together. The idea came from the ‘Conan the Barbarian’ pit and John Milius. That was just talk. That was never going to happen.”

Davie admits there was talk of a pit, and a moat was actually

discussed, as was lowering the “Cage of Death,” which was going to

dramatically descend from the arena ceiling. He also backed up

McCarthy’s claim that there was a discussion about electrifying the

fence.

“We thought about that to shock the fighters if they tried leaving,” Davie said. “That was ruled out in fear of a sweaty fighter having a heart attack if they landed on the electrified copper ring. Yes, we spoke about all of those things, because we wanted to add as much risk and danger to it as possible.”

In the end, it was all wiped out, save for the Octagon, now a staple of the UFC.

Now came the hard part: finding the fighters. Davie opened his voluminous phone book again and began cold calling. Mike Tyson, at the time universally recognized as “the baddest man on the planet,” was in prison serving his rape conviction and would have been far out of Davie and his group’s price range. Davie tried former heavyweight champion and Ali conqueror Leon Spinks, who once was reduced to making a buck squeegeeing the glass panels at St. Louis’ Scottrade Center. He was not interested. Davie contacted Dennis Alexio, a kickboxer who played Jean Claude Van Damme’s brother in “Kickboxer.” He, too, declined.

Photo: D.

Mandel/Sherdog.com

Gerard Gordeau was asked to represent savate, but

he was kyokushin through and through.

Davie and Meyrowitz tried every outlet and every way conceivable to cobble together a roster. They took out ads in “Black Belt” magazine, “Inside Karate” and “Playboy” -- any way to get the word out to prospective fighters.

Davie burned the phone lines trying to mine that perfect mix that would fit well with what the Gracies envisioned. In the United States, mixed martial arts was not practiced before wide audiences prior to UFC 1. There was no genuine template to follow.

Patriarch Helio Gracie came to the United States with the intention of opening the country’s eyes to Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. His sons took turns carrying their father’s torch.

“When I met the Gracies and their father, Helio Gracie, as the whole thing was happening, they were trying to get people to come to their dojo, and the whole purpose of the first UFC, regardless of what anyone tells you, it was geared toward the Gracies and Gracie Jiu-Jitsu,” McCarthy said. “Look at Rorion and the other sons. Before there was anything called UFC, we were going to martial arts shows and high school gymnasiums and introducing people to Rorion Gracie and to sell Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. It was originally intended to be an infomercial, a live infomercial about Gracie Jiu-Jitsu.

“Helio was the one godfather of MMA, not Bruce Lee, who a lot of people who don’t know like to say,” he added. “Helio Gracie fought real fights. Bruce Lee was an actor who fought in the movies and on TV. Helio Gracie fought real fights and took on Masahiko Kimura. Helio would fight anyone and is the true godfather of what MMA is today.”

There was, however, one clandestine Gracie edict, according to Davie.

“No wrestlers; the Gracies didn’t want anything to do with wrestlers,” he said. “That limited us a little more. We were trying to sell a bunch of guys on something they never heard of, with the exception of the Gracie name. I brought in guys from Japan that were considered to be national idols, but it was the wrestlers that freaked out Rorion a little. The Gracies knew they could beat anyone associated with mixed martial arts.”

They were not so sure about wrestlers, which is why two-time Olympic gold medalist Bruce Baumgartner, Olympians Mark Coleman and Dan Henderson and of pair of collegiate All-Americans, Mark Kerr and Randy Couture, were never asked to compete.

“Pro karate shaped the way I fought. I won several big tournaments; think about it,” Frazier said. “We were going to compete in Colorado, right near the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, and there were no wrestlers involved? I remember at the fighter meeting before the event, Rorion told me all the wrestlers declined to fight.

“My reality at that moment: wrestling was a key thing to learning, because no one had an answer in martial arts for a double-[leg] takedown,” he added. “It’s why I believe the Gracies didn’t ask any wrestlers to compete. You had some of the top wrestlers in the world right there in the backyard of where this thing was taking place. The Gracies wanted no part of them, not one bit. At the time, I believe it was a disservice to MMA.”

Photo: D.

Mandel/Sherdog.com

A miniature replica of the UFC 1 Octagon in Rorion

Gracie's Gracie Museum in Torrance, Calif.

Rosier, on the backside of his kickboxing career, saw one of the magazine ads. He was the perfect foil for what the Gracies and Davie were in search of: a serviceable fighter who was passed his prime.

Dutch star Gordeau wore the title of savate champion in 1991. He would be dangerous.

Tuli, also known as Taylor Wily, was more noted for his peripheral role as Kamekona on “Hawaii Five-0.” He had a sumo background but had been removed from the sport for four years when WOW and the UFC 1 people called. Tuli was by far the largest competitor -- and possibly most astounded by what was about to transpire.

Shamrock was still in the prime of his career. His entry legitimized the event, especially after his victory in the first Pancrase, where he choked out Japanese legend Masakatsu Funaki on Sept. 21, 1993. Shamrock thought he was in for easy money, that the $50,000 was his. He found out different.

Finally, word was spreading.

“When I first heard about it, I thought it was nuts, absolutely nuts,” MMA great Bas Rutten said. “Gordeau was a friend of mine from Holland, and I didn’t know he was going to fight. I remember seeing Ken Shamrock in September at the Pancrase in Japan, and he was telling me about this tournament without any rules and no referees. I told him I didn’t think it was such a good idea.”

Rutten’s initial thought was that UFC 1 was going to be like “Rollerball,” the 1975 cult favorite starring James Caan, only without the motorcycles and roller skates. Everything else was there to satisfy the combat sports fan’s desire for violence.

“At that moment, I was not for it,” Rutten said. “My biggest concern, as I understood them, was there were no rules and no referees. I thought that it was too dangerous. That was it; not for me. You always hear these fighters say they’re prepared to die in the ring. In reality, what we do is professional, like playing basketball or football. You compete. It’s professional, and that’s what fighting should be. A lot of times it is just talk or it’s stupidity to say you’re willing to die in the ring.

“I wasn’t going to risk my life doing that,” he added. “I was having a great career at the time in Japan. I didn’t need that. My career was going. You want to know what eventually got me into the UFC, after they got rules, of course. It’s the craziest reason anyone went into the UFC. I did it because I liked the entrance music. It still gives me goose bumps.

Rutten was not alone in his concern.

“A lot of guys wanted to wait and see what happened, and a lot of guys were like me: without any rules, no refs, you’re going to get matched up against some asshole who may not know when to stop hitting you when you’re down,” he said. “You could have gotten seriously hurt. It’s why I give all of those guys in the first UFC a lot of credit. They were all taking a huge risk.”

Frank Shamrock, who in 1999 became the UFC’s first middleweight champion, shared similar reservations.

“It just seemed crazy to me, too,” he said. “I was really an athlete at the time and I saw those ads, style-versus-style, and it was insane. The first time anyone asked me about that, I said, ‘Hell no, a lot of guys weren’t going to do this.’ You could tell they were trying to do something over-the-top with what they were doing. I thought someone was going to get hurt.”

Finish Reading » As the fighters were taken care of with transportation, hotel accommodations, the fighter meetings, Shamrock kept harboring the thought that, at any time, the hammer was going to fall, the rug was going to get yanked from under this grand idea.

Related Articles